Compliance with US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) labelling regulations has generally meant that a product is immune from a claim that its labelling is deceptive or misleading with respect to statements sanctioned by those regulations. That may soon change if the US Supreme Court sides with POM Wonderful in a dispute with Coca-Cola regarding the labelling of its Minute Maid “Pomegranate Blueberry” juice blend. If the ruling, expected this month, is in favour of POM Wonderful then food and beverage companies will need to rethink their marketing and labelling practices.

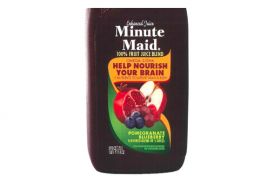

The case began in 2008 when POM alleged that Coca-Cola was misleading consumers about the contents of its Minute Maid “Pomegranate Blueberry” juice (with “Flavored Blend of 5 Juices” in smaller font below). POM claimed the label was misleading because, despite the name, the product contains very little pomegranate or blueberry juice and consists, instead, of approximately 99 per cent apple and grape juice, which is less-expensive (specifically, 99.4 per cent apple and grape juices, 0.3 per cent pomegranate juice, 0.2 per cent blueberry juice, and 0.1 per cent raspberry juice). Based on this contention, POM asserted claims under the federal statute governing false advertising and unfair competition (the Lanham Act) as well as similar provisions under California state law.

POM has extensively promoted its juice products as having various health benefits and the names of its juice blends reflect all of the juice in a particular product. For example, POM’s “Pomegranate Blueberry” juice is made from 85 per cent pomegranate and 15 per cent blueberry juices. From POM’s perspective, Coca-Cola was unfairly riding on the coattails of POM’s advertising and marketing with a non-comparable product and POM was losing sales as a result.

In its defense, Coca-Cola argued that the images on its product correctly identify the five fruits in the juice blend and that the name – “Pomegranate Blueberry – flavored blend of 5 juices” – informed consumers as much while describing that the blend tastes like pomegranate and blueberry. In this regard, Coca-Cola said that such labelling complied with FDA juice-naming regulations permitting a beverage to be named after a non-predominant juice in such circumstances. Accordingly, POM was impermissibly challenging FDA regulations permitting the name and labelling that Coca-Cola used.

The lower court accepted Coca-Cola’s arguments and rejected POM’s state-law claims as being expressly preempted by federal law under the Federal Food Drug and Cosmetics Act (“FDCA”). In other words, because the juice’s name and label were expressly authorised by the FDCA and FDA’s detailed implementing regulations specific to flavoured juice blends, POM’s state-law claims sought to impose different “requirements” than federal law. And state laws that conflict with federal law are “without effect” pursuant to the Supremacy Clause of the US Constitution.

But the same legal principle did not apply to POM’s claim under the Lanham Act which, like the FDCA, is a federal statute. Nevertheless, this claim was rejected because, according to the lower court, doing otherwise would “disturb” the “comprehensive food and beverage labeling regulations under the FDCA which specifically considered the naming of such juices.” The court felt that, given the FDA’s expertise in this area, the FDA was free to act if it believed that more should be done to prevent deception, or that Coca-Cola’s label misleads consumers. Its ruling was upheld by Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Significantly, neither court reached the question of whether the label was actually deceptive and/or misleading to a reasonable consumer.

In January 2014, however, the US Supreme Court agreed to hear the case. The specific legal question at issue is whether a private party can bring a Lanham Act claim challenging a product label regulated under the FDCA, or, more narrowly, whether a Lanham Act claim may challenge a product name and label specifically authorised by FDA regulations issued under the FDCA. From POM’s perspective, mere compliance with FDA regulations should not provide a safe harbor from claims of false advertising and unfair competition. Coca-Cola, on the other hand, believes that because the naming of juice blends was specifically considered and regulated by the FDA, statements authorised pursuant to those regulations cannot, by definition, be deceptive or misleading.

During oral argument before the Supreme Court in April, the justices seemed to side with POM. Specifically, they expressed concern about labels that comply with FDA regulations but that may also be misleading. As stated by Chief Justice John Roberts, who took the view that the FDA’s expertise is more focused on health than consumer deception: “I don’t know why it’s impossible to have a label that fully complies with the FDA regulations and also happens to be misleading on the entirely different question of commercial competition, consumer confusion that has nothing to do with health.” Similarly, Justice Anthony Kennedy disagreed with Coca-Cola’s assertion that consumers were sophisticated enough to know that other juices would be in the bottle because the food label contained the word “flavored” (a term of significance under FDA regulations): “Don’t make me feel bad because I thought that was pomegranate juice.” At another point, Justice Kennedy said: “I think it’s relevant for us to ask whether people are cheated in buying this product.” And when Coca-Cola’s attorney disputed that the label was misleading, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg asserted, “Suppose that the reality is that consumers are misled.”

Based on the oral argument, most observers expect a ruling in POM’s favour, which would significantly alter the existing legal landscape by removing, at least to some extent, the “safe harbor” for statements explicitly authorised by FDA regulations. In that event, it is imperative that food and beverage companies re-evaluate their labelling practices to assess whether any product might be susceptible to a claim that its label is false or misleading based, in whole or in part, on FDA-approved statements and names. That advice is especially important for juice blends where a non-predominant juice is used in the product’s name. Given the large number of lawsuits targeting food companies for their labeling practices and the incentives for filing such suits, it is important to understand what labels are potential targets.

In this regard, most food and beverage companies do an excellent job of complying with FDA labelling requirements. But they too often fail to fully assess the risks of combining those approved statements with other marketing statements and imagery on the product. In this case, the front of the Minute Made product includes the statement “Nourish Your Brain” along with large images of a pomegranate and blueberries (along with, admittedly, apples, grapes, and raspberries). This likely increased POM’s view that, when combined with the name Pomegranate Blueberry, consumers were being misled.

Simply put, the product, especially the front of package standing alone, must be assessed as a whole to determine if it might convey a misleading impression to a reasonable consumer. If the answer is “yes,” then the risks of continuing with that packaging and labelling must be fully measured.

David Ter Molen is a Partner at Freeborn & Peters in Chicago as serves as a member of the firm’s Litigation Practice Group and Food Industry Team.

No comments yet