Fruitnet has spoken exclusively to Fernando García-Bastidas, the scientist responsible for confirming Latin America’s first known cases of Panama disease, which were found in two banana plantations in La Guajira, northern Colombia, in Juneand officially confirmed earlier this week.Originally from Colombia himself but now living and working in the Netherlands, García has worked closely with government agency the Colombian Agricultural Institute to analyse samples that he took in person while on location in the country back in June.

Fernando, can you please explain how the process of testing for TR4 in these two Colombian banana plantations works? What precisely have your test results shown? And what specifically was the implication of the second set of results?

Fernando García-Bastidas: To fully confirm the identity of the fungus in a way that is acceptable for the scientific community, as well as preventing false positives, involves three steps.

Firstly, molecular diagnostics. Here, we use a small part of the genome, and we use something called a primer that is unique to the TR4 sequence. The process is called PCR, which stands for polymerase chain reaction, and is quick to do. In fact, I did it together with the Colombians in Colombia during the week I was there.

This Is not 100 per cent certain, as it can sometimes provide false positives. We also did additional molecular diagnostics with quantitative PCR and a technique called loop mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP). This gave positive results, so we informed ICA and they took immediate action. However, based on this it remains difficult to be 100 per cent sure: what happens, for example, if it is another race? What if you eradicate dozens of plants and it is not TR4? Of course, in better cases it may be a strain associated with the subtropical race 4, although this is also a big problem.

Anyway, to confirm, the second step is a more reliable test. There are two: a laborious lab technique from the 1980s called VCG, or nowadays we can just sequence the whole genome of the suspicious fungus. With this test we were able to compare the Colombian isolate with the existing TR4 incursions, of which there are around ten, from Jordan, Lebanon, Pakistan, Laos, Vietnam, China, Myanmar and so on. We also include race 1 and other Fusarium strains of course. With this test, we can confirm that the Colombian isolate is more similar to the TR4 strain than to strains associated with other races, like race 1, subtropical, race 2 etc.

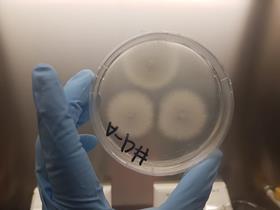

The third and final step – still ongoing – is the pathogenicity tests. These is done to complete Koch’s postulates (four criteria designed to establish a causative relationship between a microbe and a disease). In short, we need to confirm that the isolate I brought back from Colombia is able to infect bananas here in greenhouse conditions. After that, I need to isolate the fungus from those plants again and prove that it is the same as the original. As you can see, it is a lot of work that we did in record time. I brought 22 plant samples back with me from Colombia and out of these I isolated more than 50 colonies.

As a Colombian, this must be a hard thing to see. Are there any positives to be taken as the country looks to tackle TR4 in the future?

FGB: Yes, I was heartbroken and it’s been a very hard month with little sleep and a lot of thinking. It’s a big responsibility being in charge of this situation, as it is the first incursion in Latin America and it happened in Colombia. I don’t see anything positive coming out of this situation unfortunately, only bad. It is a risk for many banana farmers and not only for the industry. A lot of money has to be invested now in keeping the disease controlled – money that could be used for other purposes like research or education, for example.

Latin America has been waiting for this moment, but we did not expect it to be so quick. What this situation shows is that, even though Latin |America thinks it is prepared for this, it is not. Hundreds of plants and many hectares have to be destroyed now. I’ve seen a lot of protocols and videos published around there, but in reality when you visit these areas it’s another story. It is a fact that the pathogen did not arrive in June; it was already there for several months at least. But it is unnoticeable until it shows up with symptoms that are visible externally, which is why we need to enforce rapid diagnostics in asymptomatic plants as part of the surveillance plan. The disease moves quick and faster in infested soil, and soil is something we can’t prevent – it can be attached to containers, shoes, tools and machinery.

The good thing is that it happened in a big farm with good resources in terms of money, so they are doing as much as possible to contribute to solve this problem, even eradicating thousands of plants that probably are not infected yet. It could have been worse had it happened to small farmers or in the plantain areas. We need to speed up research in terms of diagnostics, and look more into epidemiology and more importantly breeding for resistance.

A full report on the TR4 outbreak will be published in the September 2019 issue of Eurofruit Magazine. To reserve your copy, contact subscriptions@fruitnet.com or call +44 20 7501 0311.

No comments yet